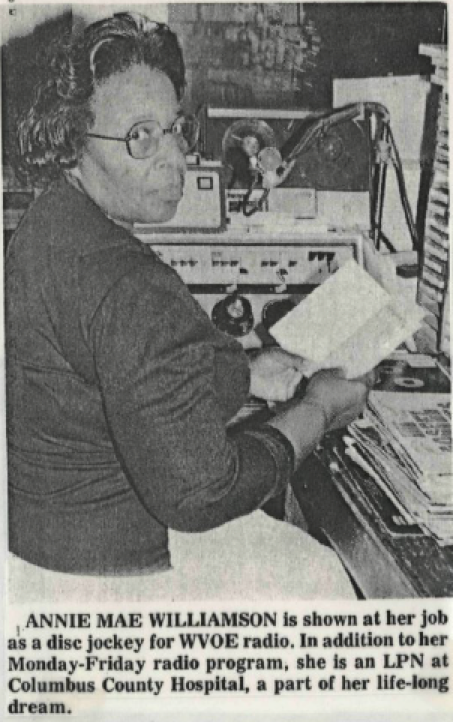

ANNIE MAE WILLIAMSON: LOCAL RADIO PIONEER FOR FIFTY-ONE YEARS AND COUNTING

This is part two of our series on WVOE-AM.

Annie Mae Williamson is ninety-four years old. She has been hosting The Women’s Program five-days-a-week on WVOE-AM in Chadbourn, North Carolina, ever since Ted. Reynolds knocked on her door in 1962. Mr. Reynolds, a founder of WVOE (“The Voice of Ebony”), marched right up to Annie Mae Williamson’s home one day over fifty years ago to propose that she pioneer a segment for women on the newly founded black-owned station, only the fifth of its kind in America. In an interview with Joshua Davis, Williamson describes that fateful day Mr. Reynolds approached her with his broadcasting opportunity.

AW: In 1962, when the radio station came on-air, Mr. Reynolds, which was the manager, he came to my home one day. He said, “Mrs. Williamson, I want to do a woman’s program, and I want you to host it.” I said, “Mr. Reynolds, I have no, you know, knowledge of—.” He said, “You can learn!” And so, that’s the way it started. I came on out, and he told me what he wanted me to do, and I just started from that. I learned. You know, as you go along, you learn.

JD: Why do you think he came to you, of all women in Chadbourn?

AW: Well, I guess somebody must have told him—Mr. Walls, I think, was here at the time. And evidently, he probably asked Mr. Walls. And at that time, I was in the church with Mr. Walls, and he knew my capability, I guess. He knew what I stood for.

In 1962 Ms. Williamson had already worked as a midwife for the Columbus County Health Department for sixteen years, and she was quite active in her local congregation. Half a century later, she still offers household hints and advice on health issues over the air, with as many as fifty calls from listeners in a single hour. You can tune into Annie Mae’s show from Monday through Friday from 11am to noon on 1590 on your AM Dial in the southeastern corner of North Carolina..

Click HERE to listen to an excerpt of an interview with Annie Mae Williamson conducted by Josh Davis.