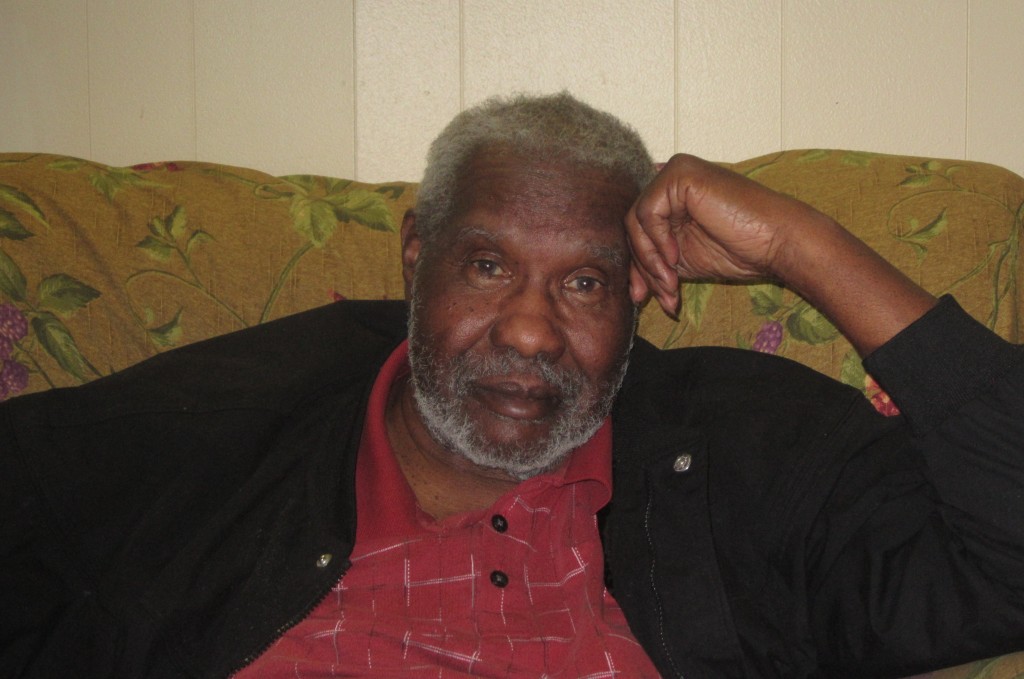

Jeffrey Starkweather, born into a conservative Christian household in California, eventually made his way to Washington, D.C. where he worked as a staffer and organizer, developing the community-mindedness that would eventually take him to Pittsboro, North Carolina in the early 1970s. There, he took over the Chatham County Herald, a paper serving this fairly rural county in the North Carolina Piedmont.

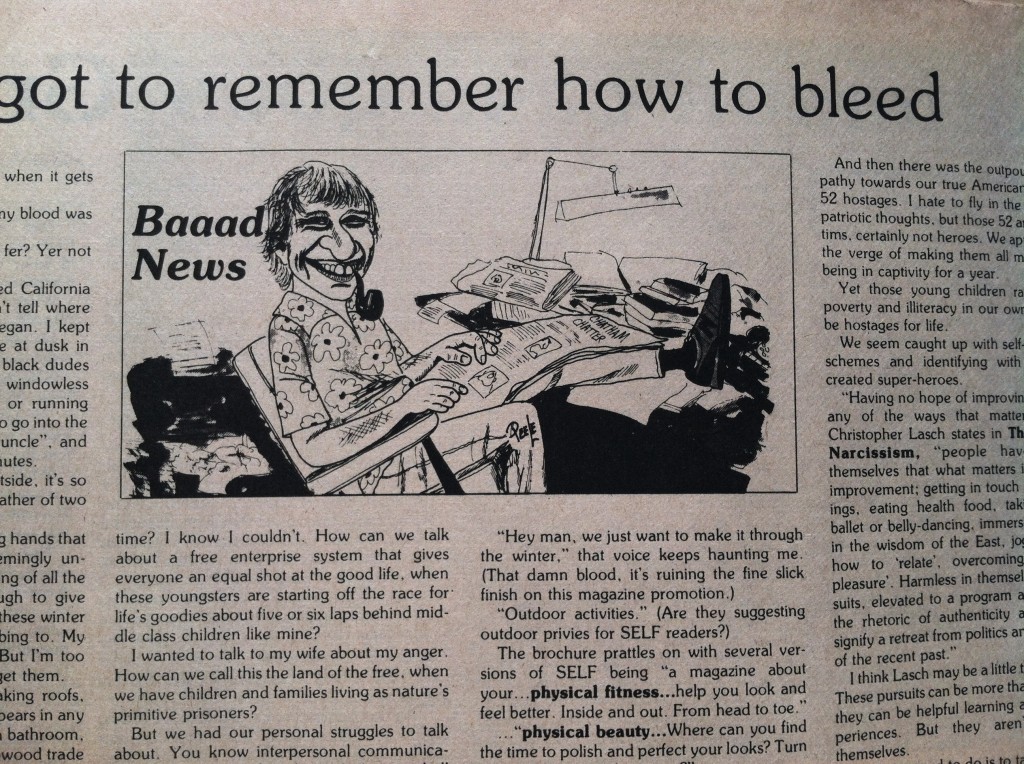

Jeffrey Starkweather depicted in the header for his column, “Baaad News.”

Starkweather quickly shocked county leaders by actually covering community issues and political proceedings, a standard journalistic practice not often employed before his arrival. The Herald was not an alternative paper. That is, it did not exist to provide an alternative source of journalism and information for a community already being served by a local media outlet. Chatham County residents read The News and Observer of Raleigh, as did many North Carolinians, but they did not have a local paper to call their own. Starkweather set out to provide one, covering sports, church gatherings, local events, and other local news as well as pursuing investigative reporting.

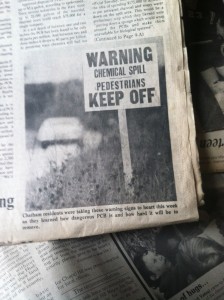

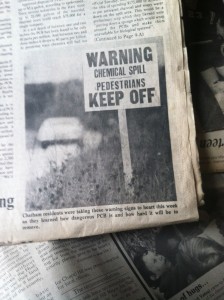

A photograph in an August 1978 issue of the Chatham County Herald indicates residents’ concerns with the health effects of PCBs illegally dumped in the area.

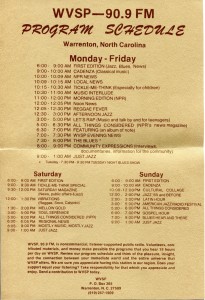

Within just two years, the paper had won two major journalism awards for its investigative and community work. At the end of the 1970s, the Herald’s coverage of plans to deposit soil contaminated with PCBs in Chatham County successfully halted that effort (the contaminated soil was dumped in Warren County, the home of WVSP), demonstrating the power of local media in addressing and affecting policies and practices with local impact.

Starkweather’s desire was to use the Herald to shed light on the political process, thus contributing to the community’s civic health, but also to acknowledge the importance of the daily lives of Chatham County residents. He describes his philosophy here:

(Don’t see the audio player? Try Safari or Firefox. Or use the QR code below.)