Stokely Carmichael, Amiri Baraka, and H. Rap Brown

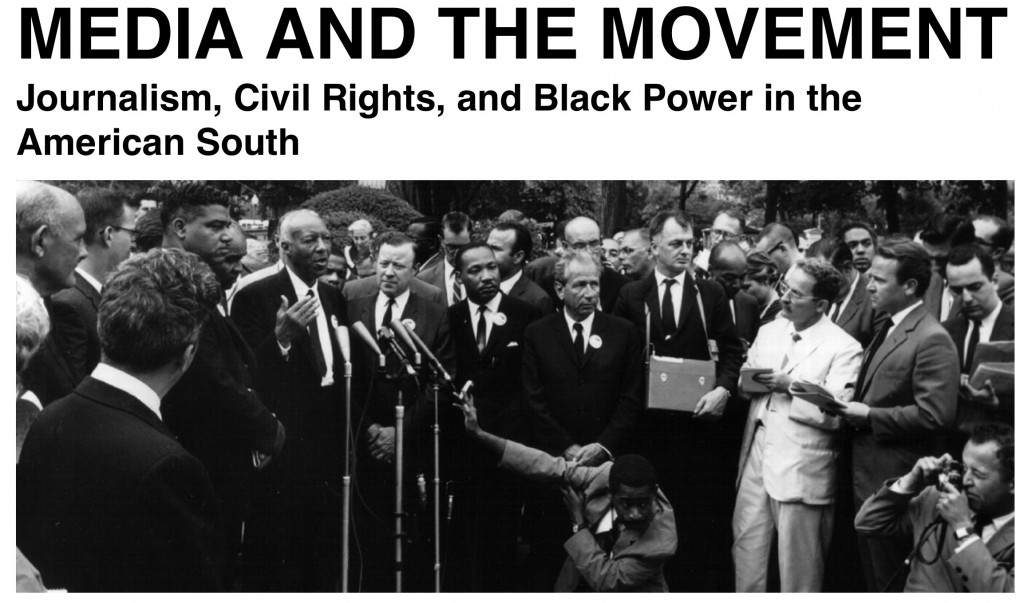

As Amiri Baraka passed away one month ago today, it’s worth reflecting on the artist-activist’s complex and multifaceted contributions to the media and the movement. Many of Baraka’s obituaries, including ones from NPR , The Washington Post, and The Los Angeles Times, described him as a writer first, a leader in the Black Arts movement second, and a political figure third (Democracy Now’s excellent coverage was a key exception). Journalists recounted Baraka’s involvement with political movements merely in passing, almost as if they were distractions from his literary and artistic career. Most obituaries did not even mention what was arguably the high point of Baraka’s political career, his election as chairperson of the 1972 National Black Political Assembly, when a broad coalition of tens of thousands of African Americans converged on Gary, Indiana to discuss forming their own national political party.

As James Smethurst wrote in his seminal work, The Black Arts Movement, it is “commonplace to briefly define Black Arts as the cultural wing of the Black Power Movement…[but] one could just as easily say that Black Power was the political wing of the Black Arts Movement.”[1] This idea certainly applies to Baraka. Most obituaries framed his political work as an outgrowth of his writing, but one could also argue that Baraka’s written work–especially in his black nationalist period stretching from roughly 1965 to 1975–grew out of his politics.

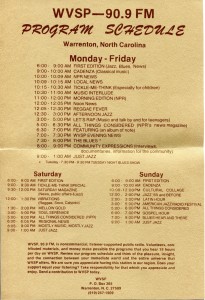

Historians such as Komozi Woodard have convincingly argued for Baraka’s significance as a central figure of both the black nationalist and pan-Africanist movements, as well as a national leader in Marxist circles. Baraka was also a publisher and editor of various black nationalist and radical magazines and newspapers, including The Cricket, Black New Ark, and Unity and Struggle, and he lent his support to Newark’s black nationalist publishing house, Jihad Productions.

The video below gives a glimpse of just how deeply Baraka participated in black politics and media making in the early 1970s. It comes from Breaking the Chains of Oppression, a rare documentary about the first commemoration of African Liberation Day, when an estimated 50,000 demonstrators assembled in Washington, D.C. in May 1972 to demand black independence in the U.S. and abroad. The driving force behind ALD and the producer of the documentary was the African Liberation Solidarity Committee, a group with which Baraka worked closely.

Baraka was well acquainted with Black Power activists in the South. In 1970, he helped to found the Congress of Afrikan Peoples at the group’s inaugural meeting in Atlanta. The ALSC was also active in the South, particularly North Carolina. Although it was headquartered in Washington, it was led by the Durham-based activist Owusu Sadaukai (Howard Fuller) and worked closely with Greensboro’s Malcolm X Liberation University and the Student Organization for Black Unity.

[vimeo]https://vimeo.com/85574042[/vimeo]

[1] James Smethurst, The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 14.