SAM GREENLEE AND THE SPOOK WHO SAT BY THE DOOR

Media and the Movement was sad to learn that writer Sam Greenlee passed away at the age of 83 on May 19. Greenlee was best known for his 1969 novel The Spook Who Sat By the Door, a semi-autobiographical account of the CIA’s first black agent based on Greenlee’s own experiences with the U.S. Information Agency from 1957 to 1965. After years of tolerating racist and demeaning treatment from his white superiors, the disgruntled agent Donald Freeman leaves the CIA and sets out to put his paramilitary and intelligence training to new use. Freeman relocates to Chicago, where he organizes a group of young black gang members and gives them a radical political education and military training so they can launch an armed revolution in the city.

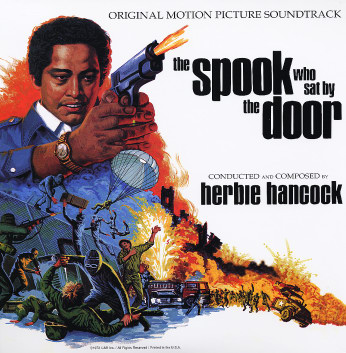

Following the novel’s release, Greenlee produced a screenplay for a film adaptation, which was directed by Ivan Dixon and released in 1973. The film is nothing short than astonishing. Not only does The Spook Who Sat by the Door forward a radical, Black Power ethos virtually unseen in other movies of the era, but Greenlee and Dixon also shot parts of the film guerilla-style in Chicago without permits from a Ricahrd Daly-era City Hall. Interestingly, Mayor Richard Hatcher’s office gave Greenlee and Dixon’s crew full permission to film other scenes in neighboring Gary, Indiana.

Yet The Spook Who Sat by the Door flopped at the box office and was reputedly removed from national circulation at the demands of the FBI. One pristine print survived and resurfaced in 2004, however, and the film was placed on the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 2012.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SLKSyy5AwtQ[/youtube]

The trailer for The Spook Who Sat by The Door gives a good preview of the film’s narrative and political trajectory. Particularly notable are the film’s gestures to Leftist, Pan-Africanist, and Third World revolutionary ideology. The young Chicago revolutionaries’ struggle, Donald Freeman explains, is one of “men against machines, brains against computers. Now if you don’t think it can work, then check out Algeria, China, Korea, and the ‘Nam. Can you dig it?”

Out of circulation from 1974 to 2004, The Spook Who Sat By the Door is now viewable in its entirety online.

R.I.P. Sam Greenlee, 1930-2014.