The civil rights and black power movements of the 1960s swept through the American South like a storm, leaving behind a profoundly changed environment. The boundaries drawn by racial segregation were washed away, and although those boundaries were often redrawn in less overt ways, African Americans in the South were by the late 1960s able to take unprecedented control over their public lives. As they began to seize control of their communities and reckon with their new freedoms, the national media, so crucial in publicizing the civil rights movement and encouraging widespread support for the demands of the protestors, retreated to their respective cities to begin their chronicle of the malaise of the 1970s.

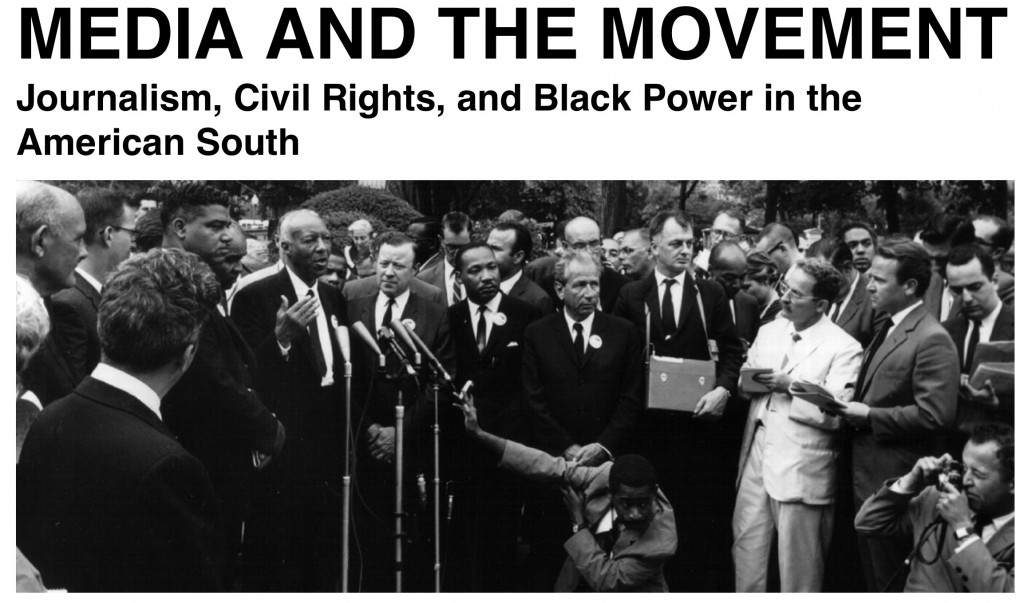

The withdrawal of these media left space for a group of southerners transformed by the civil rights movement but hungry for more change and for the opportunity to tell their own stories. These southerners left behind a remarkable and largely forgotten record of what came after the more famous Montgomery-to-Memphis phase of the civil rights movement that ended in 1968. The Southern Oral History Program’s Media and the Movement project will interview roughly fifty journalists who covered, debated, and even shaped how civil rights and black power struggles transformed the South in the 1960s and 1970s.

This study will be the first research project that examines a civil rights-era local southern media ecosystem in its entirety. In addition to publishing recordings and transcripts of interviews online, project collaborators will produce referenced, interpretive commentaries for each interview. Thus, this project will provide both scholars and students with accessible, provocative, and illuminating historical analysis on an overlooked dimension of the civil rights movement and its long-term impact on southern life.

Media and the Movement: Journalism, Civil Rights, and Black Power in the American South is directed by Joshua Clark Davis, Ph.D. of Duke University and Seth Kotch, Ph.D. of the University of North Carolina’s Southern Oral History Program in the Center for the Study of the American South in collaboration with Charmaine McKissick-Melton, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Chair, Department of Mass Communication at North Carolina Central University and Jerry Gershenhorn, Ph.D., Professor of History at North Carolina Central University, and Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, Ph.D., Spruill Professor of History at the University of North Carolina. Interviews began in January of 2013.

Additional project collaborators include Joey Fink of the University of North Carolina, Gordon Mantler, Ph.D., of Duke University, and Nicole Campbell of WUNC 91.5 North Carolina Public Radio and producer for The State of Things.

We are grateful to the National Endowment for the Humanities for supporting this project with a Collaborative Research Grant, and to the North Carolina Humanities Council for a planning grant that allowed us to meet with project stakeholders and develop our application for carrying out Media and the Movement.