Yomi Moses, a Nigerian student at North Carolina Central University, leads children in singing their ABCs at a meeting of the Community Radio Workshop. Moses also gave lessons in his native Yoruban language at the CRW.

When WAFR commenced broadcasting in September 1971, it didn’t take long for listeners to discern that the station’s staffers had chosen their call letters as an homage to Africa. Indeed, with programming that celebrated African history, politics, and culture, WAFR made Pan-Africanism a main component of its programming–something that no American radio station had done before. As Obataiye Akinwole, one of the station’s founders explained in an interview for the 1995 documentary Black Radio: Telling It Like It Is, “We wanted to have our heritage in our name.”

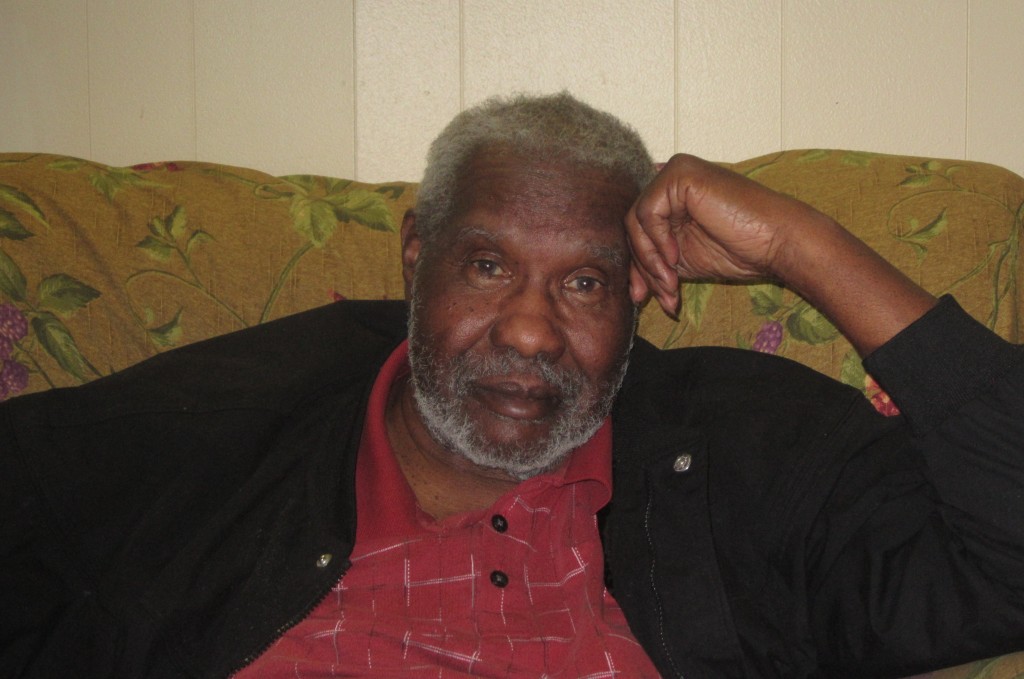

Deejays at WAFR also assumed on-air names that emphasized the group’s collective Pan-African identity, not unlike members of black nationalist groups like the Nation of Islam or Maulana Karenga’s US Organization in Los Angeles. Announcers’ names included Mwanafunzi Shanga Sadiki, Baba Femi, Brother Ola, Brother Hassan, and Johnny X. The Community Radio Workshop, the non-profit organization that administered the station, also offered public seminars on African languages and culture for adults and children. In the audio clip below, a representative of the African Reparations and Relocation Committee offers his wholehearted endorsement of WAFR’s programming

When WVSP started broadcasting several years later in Warrenton, its staff members also made international news, especially reporting on Africa, mainstays of their programming. The station developed close ties with Durham’s Africa News Service, the U.S.’s first wire service devoted to news from the African continent (more on this in a future post), and became one of its most loyal distribution outlets. Interestingly, the station’s tenure between 1976 and 1986 coincided neatly with the Soweto Uprising and the ultimate passage of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of the U.S. Congress. Consequently, WVSP frequently featured reporting on the international movement against apartheid that gained unprecedented momentum in these years, both on the air and in its newsletter, Dialogue.

A WVSP Dialogue story from 1978, provided by Africa News Service, on U.S. corporations that potentially violated a trade embargo with Rhodesia and also dealt with South African firms.