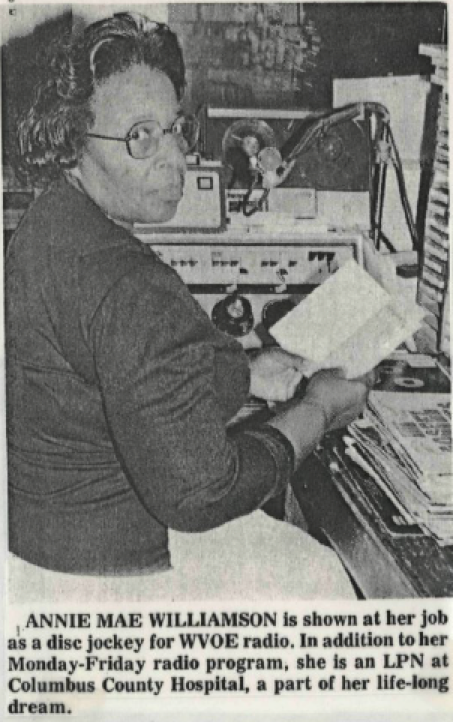

If for whatever reason you had the opportunity to pass through Chadbourn, North Carolina—located in rural Columbus County in the state’s southeastern corner, population 1,844 —you could quite possibly drive by the WVOE radio station without having any clue of its historical significance. You might not even know you were passing a radio station at all, since it’s easy to miss the antennae about fifty yards behind the station. WVOE is housed in a squat white cinderblock building about the size of a double-wide trailer, with a few staff members’ cars usually parked along a dirt driveway out front. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine a less conspicuous building.

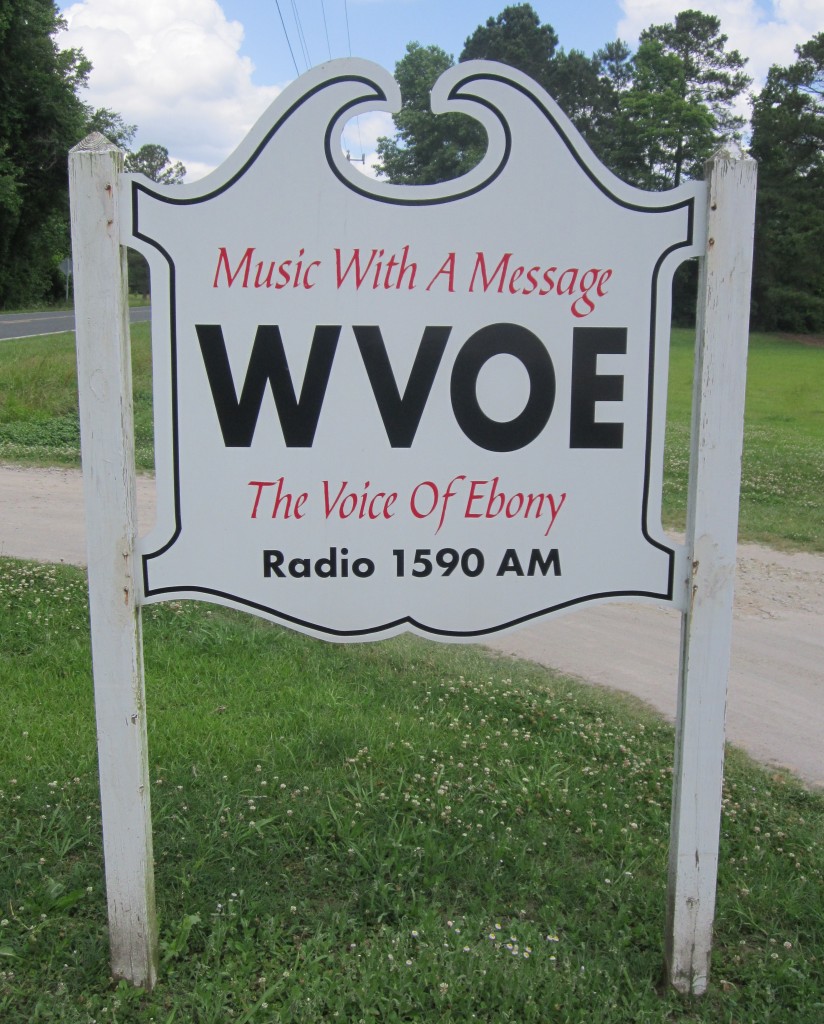

Yet a sign in front of the building announcing “Music with a Message—WVOE—The Voice of Ebony” suggests that this is no typical radio station. Borrowing their name from a popular African American magazine founded in Chicago in 1945, T.M. “Ted” Reynolds and a group of local investors formed Ebony Enterprises in Chadbourn to launch their own radio station. On April 24, 1962, WVOE, the “Voice of Ebony” began broadcasting on 1590 on the AM dial.

The station’s current president and original Sunday gospel show announcer Willie Walls recalled WVOE’s initial impact in a recent interview. In 1962, “blacks had just been turned loose more or less to freedom, and they wanted to be in the limelight of everything,” Walls argues. “To own a black radio station here in Chadbourn—that was almost something unheard of.”

Actually, it wasn’t almost unheard of—it was entirely unheard of. WVOE was the first ever black-owned radio station in rural America, as well as North Carolina’s first black-owned radio station. In fact, WVOE was only the third ever black-owned radio station in the South and only the fifth-ever black-owned radio station in the entire United States. The first, by the way, was WERD, founded in Atlanta in 1948, followed by KPRS in Kansas City, WCHB in Detroit, and WEUP of Huntsville, Alabama.

Black-owned radio, in other words, reached Chadbourn, North Carolina long before it emerged in such major media markets and black population centers as New York, Washington, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New Orleans, Los Angeles, and Oakland. Those cities and many others did have black-oriented radio stations, which targeted black listeners with music and deejay sets by African Americans. Yet like Memphis’ WDIA, the country’s first black-oriented broadcaster, the vast majority of these stations were white-owned.

The number of black-owned radio stations slowly grew to fourteen by the end of the 1960s and then rose dramatically in the 1970s, due to increased calls for black community control of radio, as well as FCC policies that encouraged minority investors to establish stations. By 1995, African Americans owned 146 radio stations in the U.S., although that number has declined dramatically since the Federal Telecommunications Act of 1996 spurred massive consolidation of radio and television ownership.

But WVOE is still broadcasting today and is still owned by Ebony Enterprises. Over fifty years after it went on the air, the station feeds its listeners a steady diet of soul, R&B, and gospel music with a healthy portion of inspirational and informational talk on the side. WVOE doesn’t stream its broadcast online yet, but the next time you’re on I-95 passing over the SC-NC state line, switch to the AM dial and see if you can pick up the 1590 signal from Chadbourn.

Watch here at Media and the Movement in the coming weeks for more posts on the remarkable history of WVOE and the “Voice of Ebony” radio.

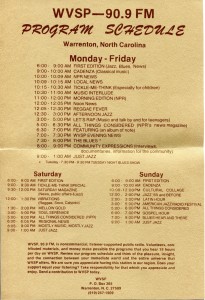

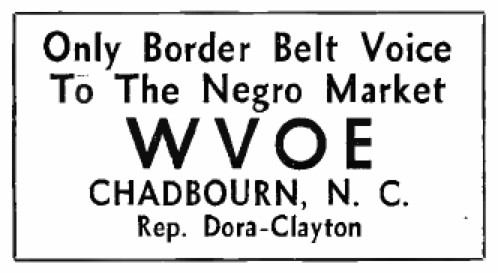

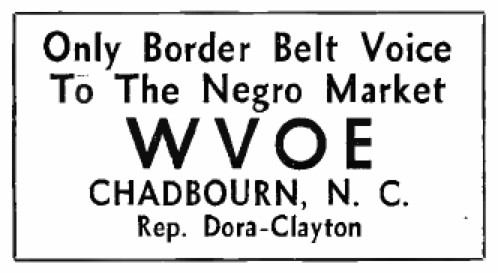

WVOE Advertisement in the 1965 edition of the trade journal Broadcasting Yearbook